|

THE PRESENTATION OF SAMURAI SWORD TO THE TOWN OF FAIRHAVEN

OPENING REMARKS

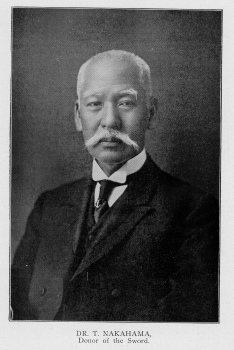

Charles P. Maxfield, Chairman, Board of Selectmen, Fairhaven. Distinguished Guests and Fellow Citizens: We have assembled this afternoon on America's greatest legal holiday to witness one of the most important ceremonies with which our Town has been favored. We have met here in accordance with the request of Viscount Ishii, the Japanese Ambassador to the United States, made to your Selectmen. He acts in behalf of Dr. Nakahama of Japan, son of Manjiro Nakahama, who was rescued with others by Captain William H. Whitfield from an island in the China sea and afterwards educated in our public schools before returning to his native country. In commemoration of that even he has come to present to our town a beautiful Samurai Sword, centuries old and of priceless value, as an emblem of gratitude and good will toward the people of the United States. WELCOME ON BEHALF OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS.

Lieutenant Governor Calvin Coolidge, Acting Governor We have met on this anniversary of American independence to assess the dimensions of a kind deed. Nearly four score years ago the master of a whaling vessel sailing from this port rescued from a barren rock in the China sea some Japanese fishermen. Among them was a young boy whom he brought home with him to Fairhaven, where he was given advantages of New England life and sent to school with the boys and girls of the neighborhood, where he excelled in his studies. But as he grew up he was filled with a longing to see Japan and his aged mother. He knew that the duty of filial piety lay upon him according to the teachings of his race, and he was determined to meet that obligation. I think that is one of the lessons of this day. Here was a youth who determined to pursue the course which he had been taught was right. He braved the dangers of the voyage and the greater dangers that awaited an absentee from his country under the then existing laws, to perform his duty to his mother and to his native land. In making that return I think we are entitled to say that he was the first ambassador of America to the court of Japan, for his extraordinary experience soon brought him into association with the highest officials of his country, and his presence there prepared the way for the friendly reception which was given to Commodore Perry when he was sent to Japan to open relations between that government and the government of America. And so we see how out of the kind deed of Captain Whitfield, friendly relations wheich have existed for many years between the people of Japan and the people of America were encouraged and made possible. And it is in recognition of that event that we have ehre today this great concourse of people, this martial array, and this representative of the Japanese people-a people who have never failed to respond to an act of kindness. It was with special pleasure that I came here representing the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, to extend an official welcome to His Excellency Viscount Ishii, who comes here on behalf of the son of that boy who was rescued long ago. This sword was once the emblem of place and caste and arbitrary rank. It has taken on a new significance because Captain Whitfield was true to the call of humanity, because a Japanese boy was true to his call of duty. This emblem will hereafter be a token not only of the friendship that exists between two nations but a token of liberty, or freedom, and of the recognition by the governments of both these nations of the rights of the people. Let it remain here as a mutual pledge by the giver and the receiver of their determination that the motive which inspired the representatives of each race to do right is to be a motive which is to govern the people of the earth. PRESENTATION OF THE SAMURAI SWORD

Given by Dr. Nakahama, of Japan His Excellency VISCOUNT ISHII, Ambassador Your Honor, Mr. Chairman, Members of the board of Selectmen, Ladies and Gentlemen: The occasion which brings me to your beautiful town today is somewhat out of the line of those official duties which are supposed to engage the attention of diplomatic officers. In reality, the pleasant task which has been assigned to me should have been given to some clear-eyed poet, some chivalric lover of humanity-whose soul was not only attuned to beautiful things, but whose art was equal to the task of giving them adequate expression. I lay no claim to these high qualifications, but I come to you rejoicing in the opportunity given me of bearing my part-however humble-in the payment of a sacred debt. The Great Book which you love, and whose precepts underlie all that is best in your civilization, says-"Cast thy bread upon the waters; for thou shalt find it after many days." Ecclesiastes, XI: 1. Upon that beautiful promise, which I interpret to mean that good things never die-that noble actions sooner or later come back in harvests of blessedness-is founded the truest incentive which men have for right living and right acting. My presence here today is the result of a generous deed on the part of one of your own townsmen. It was performed many years ago, without ostentation or hope of reward, but is proof today of his living faith in the precept which I have quoted. Let me tell you the simple story. About the middle of the last century, before Commodore Perry's historic visit opened Japan to communication with the outer world, a number of shipwrecked Japanese sailors were rescued near the Rock Islands in the China Sea, by Captain William H. Whitfield who commanded an American whaling vessel in those waters, and who was a native of this good old town of Fairhaven. This kind-hearted Captain not only took good care of these castaways, but found himself especially drawn to a bright boy among them named Nakahama. This attachment eventually grew into a relationship which was almost like that of father and son. Young Nakahama was sent to the public schools in Fairhaven and was given every opportunity to acquire western learning and a knowledge of the outside world which later stood him in good stead in the country of his birth. He finally went back to Japan where he was well received by the Government, appointed instructor of English language in a Government school, ordered to serve as assistant interpreter in the Commodore Perry negotiations, and afterwards appointed Professor of the University, Yedo. To the day of his death, Nakahama remembered with gratitude the name and the kindness of the American Captain to whom he owed so much. Now see how contagious kindness may sometimes become. Nakahama, the wrecked sailor boy, left a son who has since risen to eminence in the medical world of Japan, and to whom was bequeathed his father's sense of gratitude. This son, Dr. Nakahama, knew the story of his father's early adventures and carried in his heart through all the year a sleepless sense of gratitude. In evidence of this feeling, not only for the memory of Captain Whitfield but for the people of America as well, it finally occurred to him that it would be a graceful thing for him to present to the town of Fairhaven-the birth-place of his father's friend-some slight token of a gratitude which had survived the wear and tear of seventy years. So feeling, he has sent to me this sword with the request that I present it in his name to the town of Fairhaven in grateful remembrances of the generous act of Captain Whitfield and as evidence to the people of your town and the American people that the Japanese heart is responsive to kindness-and does not forget. I can not tell you, ladies and gentlemen, with what pleasure I respond to these sentiments of Dr. Nakahama and how much satisfaction I find in the performance of this simple duty. This gift may have little intrinsic value, but therein, perhaps, you will find its real value to consist. You are asked to receive it as the concrete token of that something which is without price and above all other values. It is tendered to you at a time in the affairs of a troubled world when men are asking if the old time virtues of gratitude and honor still hold their places in the human heart. It comes at a time when America and Japan stank linked and resolute in defense of a cause which is so holy-so just and right-that all other considerations vanish to nothingness. There is a wider significance to this grateful act of Dr. Nakahama than the simple recognition of a personal kindness. It is typical of that rising wave of sympathy and good understanding which begins to roll across the Pacific Ocean and promises to flood both lands with the sweet waters of fraternity and good will. If you will accept, in this wider sense, this token of Dr. Nakahama's gratitude, you will give it a significance in which every right-thinking and right-feeling man and woman, on both sides of the ocean, will find unalloyed satisfaction. "But why," some one may ask, "is a sword presented to this peace-loving town in recognition of an act of mercy? Does the sword not typify that which we most abhor?" There is a sense, my friends, in which the sword is typical of cruelty and wrong. There is another sense in which it stands for the loftiest conceptions of chivalric honor and virtue. To the old Samurai of Japan, whose spirit is reflected in the act of Dr. Nakahama, the sword was the symbol of spotless honor. His right to wear it signified his worthiness to use it aright. What he carried at his belt was a symbol of what he carried in his mind and heart-honor, loyalty, courage, self-control. No unworthy man might carry this sacred token of responsibility. To possess it was to be recognized as worthy to use it aright; to use it amiss constituted the brand of deepest dishonor. Dr. Nakahama, in offering you this token of his gratitude, has signified to you his perfect trust. He has endeavored to say to you that you are the worthy depositories of all chivalric honor. In no better way could a loyal Japanese as effectually tell you of his loving confidence and deep esteem. In this spirit I beg of you, Mr. Chairman, to accept for the Town of Fairhaven this tribute if gratitude. The donor would have you preserve it, not only as a monument to the memory of a good man, but as a token of Japanese good will. Dr. Nakahama would say to the descendants of those who were kind to her revered father that which the whole Japanese people would say to the people of America: --We trust you-we love you, and, if you will let us, we will walk at your side in loyal good fellowship down all the coming years. I thank you. |